Interrogating Global Humanities Infrastructure

The text of my contribution to the Critical Infrastructure Studies panel at MLA 2018, New York, January 6th, 2018.

Paul Edwards has pointed out that in its largest instantiations digital infrastructure intersects with the concept of the Anthropocene, implying that critical infrastructure studies can help us explore the relationship of human community and identity to the world in the grandest terms.1 Extending the thought of geoscientist Peter Haff, Edwards claims our digital infrastructure is entangled with a vast earth-scale ‘technosphere’ that has irremediably altered our planet’s natural balance.2 In this interpretation vast technological systems, from social media networks to climate change models, mediate our experience of reality and determine scientific understanding.

This is an insight with methodological and theoretical as well as existential implications. In previous eras we divined our relationship to the world through literature, art, folklore, myth: the building blocks of culture. Now we need to add our technological infrastructures. But how do we ‘read’ infrastructure, and especially digital infrastructure? As writers like Wendy Chun remind us, digital experience is ‘spectral'.3 It resists interpretation. It is comprised of millions of machines producing Katherine Hayles’ ‘flickering signifiers’.4 Perhaps more pointedly for our present purposes, it encourages a narrative of ‘ubiquitous computing'5 that suggests our whole world - global North and South, uninhabited tundra, deepest oceans and rain-forests - is (or is magically about to become) primarily ‘digital’.

I call this complex of obfuscating narratives, along with the socio-economic processes that enable them, ‘the digital modern’. As with many technologically inspired visions, the digital modern is characterised by the same ‘startling, unselfconscious lack of originality'6 that David Edgerton has associated with 1950s narratives about flying cars and space travel. It undoubtedly has a relationship to the Anthropocene, as Edwards claims, but its boosters give it more credence than it deserves.

In an era of fake news, advancing AI, and an emerging gig economy the digital modern appears ubiquitous, but is far from it. It is a powerful aspect of contemporary life, to be sure, but its claims to grandeur are undermined by its technical footprint, which is limited, unevenly distributed, often unreliable, and (as we are increasingly seeing, in Europe especially) open to political, legal, and cultural control.

Critical infrastructure studies exists to corral the digital modern back into its box, so that we can attend to larger issues. That, of course, is why it is being discussed at a MLA. Whether you agree with my rather cynical view of the digital modern or not, I have hopefully made the point that infrastructure studies exist to enable interpretation and deconstruct faulty representations of the world.

Before we can claim to understand global digital infrastructure we must surely seek to understand its impact on our small corner of it, though. Very little research has been done on the global digital infrastructure that enables, and probably deforms, humanities research. Whether we identify as digital humanists or merely humanists means little in the face of this engineered reality: we too easily forget, as we critique Facebook and Twitter, and rail against Elsevier, that they have become (or are fast becoming) key components of not just our cultural infrastructure but our research infrastructure. Blogs have long complemented physical diaries as historical source material, Twitter and Facebook are now fundamentally important historical texts.

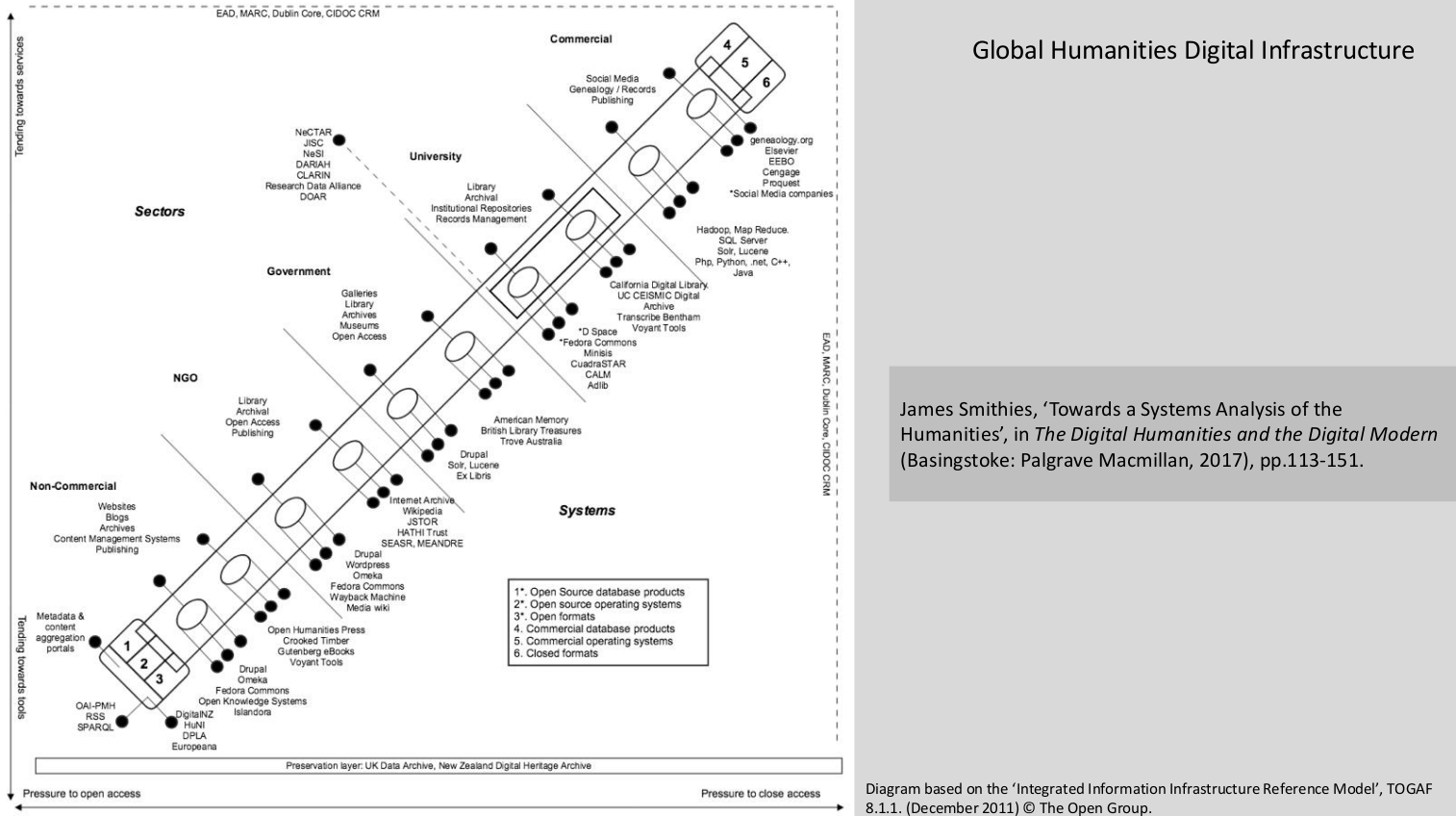

This diagram is my attempt to sketch a ‘systems analysis’ of global humanities research infrastructure to help understand it and, in doing so, influence it.7 It offers what historian of technology Rosalind Williams might refer to as an ‘engineering level'8 view, connecting its sociotechnical aspects to its scholarly purpose. It is by no means complete, and would ideally be complemented by multiple additional perspectives. As I note in the book, the model is highly conceptual. It offers a typology rather than a complete description, and should be read from the outer edges in. The goal is not to offer an exhaustive list of every digital tool or system that can be considered part of humanities infrastructure (an impossible task), but to provide a model that can be used to gain some conceptual leverage. Infrastructural components exist along two continua:

-

Open Access to Closed Access: As we move from the open Internet to the commercial Internet, the pressure to close access to content in order to monetise it increases.

-

Tools to Services: As we move from the open Internet to the commercial Internet, the nature of cyberinfrastructure tends to shift from tools that can be used for a variety of purposes towards services that must be used in a particular way.

Significant exceptions exist all along these continua. Tension is particularly apparent in the university sector, where corporate pressures prioritise the profit motive over the public good, but many researchers undertake projects that provide free open access nevertheless. There is, in this sense, no judgement implied in the model: it is merely an attempt to document a complex domain and illustrate the tensions that exist across the different sectors. The only way to deal with the inevitable inconsistencies is to document dominant tendencies and follow up with an analysis that explores why such inconsistencies exist.

If the diagram has value for the humanities community I hope it is less in its specifics - its attempt to chart the mess of reality onto a postage stamp - than as a reminder that we need to actively research, explore, and understand the effect digital infrastructure is having on our work so that we can take part in conversations about it at our institutions and across our scholarly communities, and maintain what we have in a more effective and transparent way. It is one thing to point to the obfuscating effect fake news has on our politics, quite another to ask what effect our newly deployed digital infrastructure is having on our interpretation of the world. Some of the readings that result will be unavoidably technical, but they should also expose the system to cultural and political critique.

Infrastructure studies needs to look outwards towards the Anthropocene, but we also need to direct our gaze inwards. We need to use the tools and methods of infrastructure studies to understand our collective epistemological and methodological condition, and to empower humanities research communities to chart their own digital futures. That will require a genre rather than a single chapter, a new mode of reading that can account for our engineered as well as creative realities.

1 Paul Edwards, ‘Knowledge Infrastructures for the Anthropocene’, The Anthropocene Review 4, no. 1 (April 1, 2017): 34–43.

2 Peter K. Haff, ‘Technology as a Geological Phenomenon: Implications for Human Well-Being,’ Geological Society, London, Special Writing 395, no. 1 (January 1, 2014): 301–9.

3 Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed Visions: Software and Memory (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), p. 17.

4 N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 30.

5 Paul Dourish and Genevieve Bell, Divining a Digital Future: Mess and Mythology in Ubiquitous Computing (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014).

6 David Edgerton, Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History Since 1900 (London: Profile Books, 2011), p. xvi.

7 James Smithies, ‘Towards a Systems Analysis of the Humanities’, in The Digital Humanities and the Digital Modern (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp.113-151.

8 Rosalind H. Williams, ‘Opening the Big Box’, Technology and Culture 48, no. 1 (2007): 104–16.